By Adam Wasserman

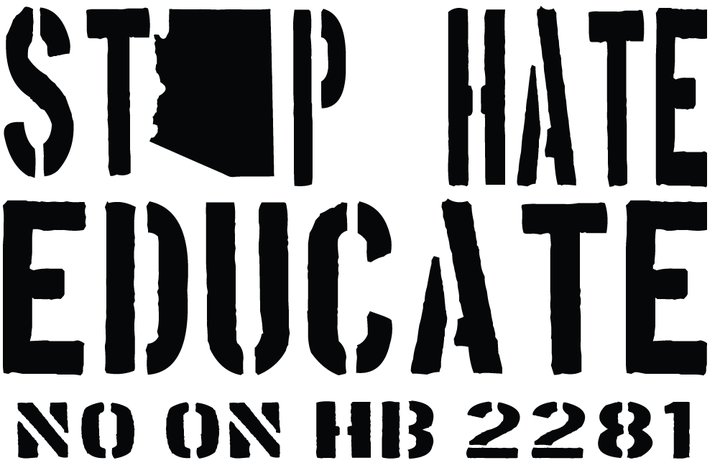

History is becoming a political and social battleground. There is currently a struggle over how the narrative of the past is told and it reflects the great struggles and conflicts taking place on a social, political, and economic level in the country. With the far-right faction of the Texas Education Board approving a textbook curriculum that once again places the white man at the center of the past where he thinks he should be and now the largely overlooked elimination of “ethnic studies” courses in Tucson public schools that followed the recent Arizona immigration bill, the importance of people’s history and reforming traditional school curriculums is growing daily. To include the experiences of various groups of people who had been previously marginalized or excluded from traditional history curriculums also means to discuss acts of genocide, systematic theft, and injustice that reflect not so kindly on the national heroes of the past or the dominant sectors of present society. With the waning of the orthodox white male monopoly of history, the need for a new whitewash of history, in the minds of many, is long overdue. The Texas conservative curriculum and the Arizona ban on “ethnic studies” are products of a more general white backlash to the recent decades of change in the way history has been told and narrated.

The way we are told and narrated history has almost always reflected great popular trends and movements, the growing strength of particular groups who understand how their own past experiences are integral to the greater national history. Historical programs centered on the various ways that African-Americans, women, workers, and indigenous people experienced the past have garnered momentum over the past decades as popular movements have agitated for change in traditional curriculums. This very fact is what’s pushing the far-right and even many moderates and liberals to make history “objective” again, in the sense that the only “objective” viewpoint of history is a generalized one that fails to account for class, race, and gender conflict or anything that may damage the past reputation of national “heroes.” As white men now feel their long-held hegemony over history slipping away, the backlash and legislation passed has sought to solidify the “great men” theory of history in the schools, the media, and politics.

Although academia and historical authors are moving further from the “great men” theory of the past, public school curriculums are being revised to limit deviation from the “national” history that disproportionately emphasizes the role of leaders, industrialists, and powerful white men. Dissent in the orthodox historical narrative can be tolerated in the confines of scholarly debate, but not in the public consciousness. In 2006, the Florida Education Omnibus Bill passed by the Florida legislature and approved by Jeb Bush set the precedent for the more recent Texas conservative curriculum and Arizona ban on “ethnic studies.” The bill intends to solidify and make official the dominant perspective of history: the wealthy white male one. “American history shall be viewed as factual, not constructed, shall be viewed as knowable, teachable, and testable,” declares the Education Omnibus Bill, “[American history] shall be defined as the creation of a new nation based largely on the universal principles stated in the Declaration of Independence.” The bill lays out several provisions for how U.S. history is to be taught in Florida classrooms: to teach the “history, meaning, significance and effect of the provisions of the Constitution of the United States and the amendments thereto”; to emphasize “flag education, including proper flag display and flag dispute”; to emphasize “the nature and importance of free enterprise to the United States economy.” 1

But even with these recent “losses,” people’s history continues to garner momentum and expand out into various events and eras of the past in shifting perspective from top to bottom. Historians continue to cross frontiers that were widely ignored or taboo and retell historical events and eras through the words and ideas of average people on the bottom that experienced them. Since the recently deceased Howard Zinn released A People’s History of the United States in 1980 to widely popular reception and two million copies sold, history has been turned upside down. The People’s History series has released books retelling the American Revolution, the Civil War, the Vietnam War, and even World History through the words, ideas, and experiences of those on the bottom. To directly confront the Florida Education Omnibus Bill and expand people’s history to narrate the past of regional and local areas, Florida author-historian Adam Wasserman released A People’s History of Florida 1513-1876: How Africans, Seminoles, Women, and Lower Class Whites Shaped the Sunshine State. The current efforts in Florida, Texas, and Arizona to challenge this growing shift in historical perspective are also being resisted by activists and everyday people who are beginning to understand that history is a battleground.

1. Craig, Bruce. “History Defined in Florida Legislature.” Perspectives Online. Sept. 2006. American Historical Association. http://www.historians.org/perspectives/issues/2006/0609/0609nch1.cfm

Adam Wasserman is a native of Sarasota, Florida and author of A People’s History of Florida 1513-1876: How Africans, Seminoles, Women, and Lower Class Whites Shaped the Sunshine State.